Tags

Street Views: 73 and 80

Address: 32 Parliament Street and 14 Bridge Street

We saw in the post on Edward Milns that the houses along the southern side of Bridge Street had to be demolished in the early 1860s for the widening of the approach road to Westminster Bridge, but Fendall’s Coffee House had been moved once before. It used to sit against the northern front of Westminster Hall and was known as the Exchequer Coffee House. According to The Epicure’s Almanach,(1) it had existed since the 1730s and was removed in 1793, but that is dating the removal a bit too early. In 1800, Samuel Ireland is talking about the “shameful neglect” in allowing “those nuisances, the coffee houses” to be erected at the entrance to the Hall, thereby obstructing the view of the figures which adorned the front.(2) According to John Tomas Smith,

the City of Westminster [was receiving] a rapid and material improvement […] by the demolition of many shabby buildings west of the present alterations […]. At this very date, April 1807, the north front of Westminster Hall is about to resume its appearance in the time of Richard II. The two public houses, the sign of the Coach and Horses, and the Royal Oak, Oliver’s coffee-house, and the Exchequer coffee-house, which for many years disguised the Hall and Tudor buildings, have been taken down.(3)

Source: R. Dodsley, London and its Environs, 1761. Sources differ as to whether the Exchequer Coffee House was the one on the right or the one on the left of the entrance.

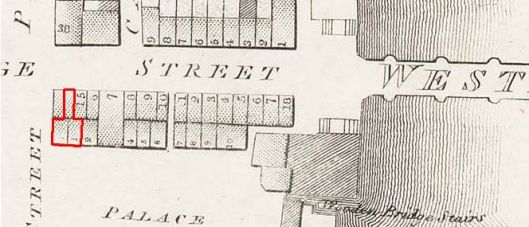

The lease of the coffee house property against the Hall had been in the hands of Alexander Lindsay, 6th Earl of Balcarres, and the under-lessee and occupier of the coffee house was one Mr. Chapman. They were compensated for the loss of the establishment.(4) In Boyle’s Court Guide for January 1829, we find Mrs Kendall of the Exchequer Coffee House at 1 New Palace-yard, 14 Bridge Street and 32 Parliament Street. No, she did not have three coffee houses; a look on Horwood’s map shows the properties interconnected and wrapped around Edward Milns’s linen drapery which was situated on the corner of Bridge Street and Parliament Street. The Parliament Street front of the coffee house can be seen at the top of this post and on the right in the vignette for Milns property in Tallis’ booklet 80 (here). The Bridge Street façade, much narrower, can be seen on the left. I have not found a picture of the Palace Yard front, but if you know of one, please leave a comment.

Who Mr. Kendall was – I presume there was one – is unclear [Postscript: yes, there was a Mr Kendall, see the comment by Gwyneth Wilkie], nor do I know when the coffee house started taking in overnight guests and calling itself a hotel, but in 1831, the hotel side of the business was definitely part of the establishment as in that year, one Charles Jones of the Birmingham Political Union wrote a letter to E.J. Littleton which was published in The Morning Chronicle of 19 April. He heads the letter “Fendall’s Hotel, New Palace Yard”. The 1841 census gives Frances Kendall, 65 years old, as the hotel proprietor at 1 Palace Yard. Also living on the premises is one Susan Kendall, 35 years old, but how they are related is not made clear.

In the 1851 census, the Exchequer Coffee House has Charles Ritchie as the 30-year old hotel keeper. He is not married, but helping him as housekeeper is Ann Page, a widow, and there is, of course, a whole host of other servants. The 1851 Post Office Directory tells us that Ritchie not only occupied the addresses Mrs Kendall had, but the business had been extended to include number 15 Bridge Street which, in the 1839 Tallis Street View, had been occupied by Mr. Gill, a glass cutter. Ritchie gets a separate entry in the directory for 15 Bridge Street as a tobacconist.

The advertisement above from The Times states that there are eight years left on the lease and that corresponds with a debate in the House of Commons on the Westminster Bridge improvements. On 5 March, 1863, William Cowper, First Commissioner of Works and Public Buildings, is asked when the houses left standing are to be removed and what arrangements have been made with the occupants for lost income. Cowper says that all the houses on the south side of Bridge Street are to be removed before the end of next year [that is 1864] and agreement had been reached with all tenants and leaseholders, except two of which Fendall’s hotel was one. The Office of Works was reluctant to pull down the hotel before it was absolutely necessary as “it was a great resort during the sitting of Parliament” and the lease was to expire in 1864 anyway, so by leaving it standing, the expense of compensation was avoided.(5)

The tenant for the last years of the hotel’s existence was Charles Brumfitt. From the list of houses to be demolished for the new approach, we can see that 14 Bridge Street was part dwelling house / part hotel; number 15 was a dwelling house and shop: the Exchequer Cigar Divan (run together with Charles Ritchie)(6); number 32 Parliament Street was a dwelling house / part hotel; and 1 New Palace Yard also part dwelling house / part hotel.(7) The 1861 census tells us that Brumfitt, his family, and the hotel staff were living at 1 New Palace Yard; the other addresses were not mentioned separately, so the census taker apparently considered the whole complex as one unit. As it had already been clear since early in the 1850s that plans were being considered to widen the bridge approach and that the Act with the compulsory purchase orders had been decided in Parliament in 1859, we can well imagine that prospected hotel guests thought it better to book their rooms somewhere else, damaging Brumfitt’s business even before the building had actually disappeared.

It is no wonder that he reacted rather fiercely in The Times of 6 January, 1863, where he states that the Daily News of the 2nd saying that “notice had been given, on the previous day, to the owners and occupiers of the remaining houses […] that they would have to vacate in the course of the month” was utterly and totally wrong and “WITHOUT FOUNDATION” [his capitals] as he was “under no notice whatever from the Board of Works or from any other quarter” and that committees, etc. requiring rooms were welcome “during the ensuing session”. It is of course true, as we have learned from Cowper’s answer in the Commons, that it was thought best to let the hotel stand as long as possible, but ‘without foundation’ is a gross misrepresentation of the situation. Brumfitt must have realised that eviction was unavoidable, although he may not have known the exact date. He may even have regretted his initial outburst as a few days later, a letter from Brumfitt to the editor was published which is couched in far more moderate wording, although we can still read between the lines that Brumfitt was not very happy about the financial compensation he was to get and had put his solicitor onto it.

Fendall’s was indeed the very last building to be removed. Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper of 15 January 1865, says that all the houses had been removed, “Fendall’s hotel, the last of them, which stood until a day or two ago, having at length disappeared”. Despite the frequent mention in the papers of the whole process of planning and carrying out the improvements to the approach road, some people were still caught out. Andrew Halliday, a Scottish journalist, when coming up to London for the debate on the Budget, took a cab and had himself set down at the corner of Palace Yard where he

“looked for Fendall’s Hotel. It was gone, and a whole row of houses with it, and had been gone, I was informed, ever so long. When I was in the habit of visiting the gallery some years since, it was my custom to fortify myself at Fendall’s before entering the House. But here I am today, wanting fortification, and there is no Fendall’s […]. Palace Yard without Fendall’s appears to me like a desert without an oasis. Where is the weary parliamentary agent to sit him down and rest?”(8)

Where indeed?

—————————–

(1) Footnote 2 on page 83 of Ralph Rylance, The Epicure’s Almanach: Eating and Drinking in Regency London, ed. Janet Ing Freeman (2012).

(2) Samuel Ireland, Picturesque views, with an historical account of the Inns of court, in London and Westminster (1800), pp. 227-228.

(3) John Thomas Smith, Antiquities of Westminster (1807), p. 267.

(4) Reports from Committees, session 1 November – 24 July 1810-1811

(5) Hansard, HC Deb 05 March 1863 vol 169 c1067.

(6) See this Londonist page for the history of tobacco in London and the first divan.

(7) The Statues of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, vol. 22. The schedule of the houses to be removed is part of Act C.58 22 & 23 Victoria.

(8) Andrew Halliday, Sunnyside Papers (1866), p. 257.

Neighbours:

| <– 33 Parliament Street | |

| <– 15 Bridge Street | 13 Bridge Street –> |

Pingback: Edward Milns, linen draper | London Street Views

I believe “Mrs Kendall” of Fendall’s Hotel to be Frances Fendall, the widow of Valentine Fendall (1769-1803). He married Frances Stevens on 29 Oct 1792 at Benson, Oxfordshire. He was a fishmonger, insured by the Sun Fire Office in 1791 at Little Sanctuary, Westminster. His widow was insured in 1804 as a victualler at The Ship, Old Palace Yard. There is a probable death record for her in 1848, in Lambeth, aged 77. This would give a birth date of c1771, as opposed to the 1841 census calculated birth-year of 1776, but ages were rounded down by the enumerators, so she could have been 69 rather than 65 as stated.

Thanks Gwyneth, that seems to solve the mystery of Mrs Kendall quite nicely. The census records, especially the early ones, were inded notoriously imprecise as regards ages, so the seemingly discrepancy is certainly not a problem.